This Wednesday (November 18), at The Global South House, amidst COP 30, in Belém, Pará state, third-sector organizations from Brazil, Latin America, Asia, and the Legal Amazon defended that a just ecological transition relies on the strengthening of agroecological and agroforestry community initiatives, led by traditional peoples, small family farmers, women, and the youth from rural areas.

This Wednesday (November 18), at The Global South House, amidst COP 30, in Belém, Pará state, third-sector organizations from Brazil, Latin America, Asia, and the Legal Amazon defended that a just ecological transition relies on the strengthening of agroecological and agroforestry community initiatives, led by traditional peoples, small family farmers, women, and the youth from rural areas.

These practices already protect biomes, generate income, and ensure food sovereignty. Despite this, they remain largely unrecognized by climate financing mechanisms.

These reflections took place during the panel, “Building a Just Ecological Transition: Financing Advanced Agroecology Initiatives for Workers and Local Communities,” promoted by Labora – Fund for Decent Work, part of Fundo Brasil, in partnership with the Louds Foundation, Ford Foundation, and Open Society.

The discussion was mediated by Ana Valéria Araújo, executive director of Fundo Brasil, who highlighted the urgency of the topic: “In Brazil, 74% of emissions are linked to land use and agriculture. Discussing ecological transition means discussing production, land, labor, and climate.” For her, “strengthening community experiences means recognizing that the solutions already exist in the territories, produced by those who live, care for, and protect the land.”

Monoculture Threatens Water and Life

Valmir Macedo, executive director of the Vicente Nica Center for Alternative Agriculture (CAV), warned about the impacts of monoculture in the Jequitinhonha Valley (Minas Gerais), especially regarding water availability. According to him, about 90% of water sources in his municipality have disappeared due to the expansion of ventures like eucalyptus plantations. “This means we are drying up what sustains life. Monoculture not only trades biodiversity for a single product but also depletes water sources,” he stated.

He championed agroecology as a concrete response: “Agroecology is, simultaneously, production, regeneration, and survival.”

Productive Power of the Territories

Silvana Bastos, technical advisor at the Instituto Sociedade, População e Natureza (ISPN), highlighted that traditional peoples and communities know about 20,000 species and manage at least 4,000 of them, while the monoculture model relies on only seven to nine cultivated species. “These territories have a production capacity much greater than we recognize. If they already manage 4,000 species, why aren’t they on our plates?” she questioned.

Bastos emphasized that, when discussing territories, they cannot be seen merely as productive ecological and social landscapes, providers of goods and services. According to her, “these places are, above all, territories of life: spaces of culture, cooperation, joy, and fundamental learning for building better public policies and for having a better COP.” It is these living landscapes that sustain the necessary foundation for agroecology to truly flourish.

Proof that Agroecology Works

Jaqueline dos Santos, from The Peoples Summit and the National Agroecology Articulation (ANA), presented unpublished data on over 500 agroecology experiences in the country. “These experiences show that agroecology works. What’s more: it is already protecting biomes, feeding communities, and sustaining local economies. What is lacking is not evidence, but recognition,” she affirmed.

She stressed that the issue is not a lack of scale, but invisibility: “It’s not that agroecology doesn’t have scale. It’s not included in the data. But when it enters the data, it shows that it can feed the country.” She concluded: “It’s not about inventing the wheel, but about strengthening the wheels that are already turning in the territories.”

Financing and Community Leadership

Representing the Samdhana Institute in Southeast Asia, Joan Jamisolamin shared experiences of Indigenous communities that link agroecology to food sovereignty and strategies to maintain people in their territories. For Joan, “communities don’t arrive empty-handed. They already bring seeds, production systems, and food sovereignty. Funding needs to recognize and strengthen this.”

Families, Seeds, and Autonomy to Act

From Nicaragua, Adela Guerrero, national coordinator of the Group for the Promotion of Ecological Agriculture (REPAE) and Tierra Viva Fund, spoke about the effects of droughts, hurricanes, and lack of access to resources. She reported that the network brings together 35,000 families and maintains 50 seed banks.

“Agroecology is not just a production method. It is an integral process that involves people, local knowledge, family, environment, and ecosystems,” she stated. She advocated for larger, direct, and less bureaucratic resources: “When funding arrives, it is often too late or reaches few communities.”

Communities as Decision-Makers

Aline de Souza Nascimento, educator at Fundo DEMA, highlighted that agroecology precedes the concept and is inherent in Amazonian ways of life. “The forest is a school that teaches how to live, not just how to survive,” she said. According to Aline, listening means recognizing that communities “already do, already know, and already transform.”

The educator emphasized community leadership in resource management: “Communities are not beneficiaries; they are decision-makers.” She reinforced the need to break colonial practices: “When resources arrive without listening and without dialogue, it turns communities into objects. And we are talking about subjects.”

The gathering signaled that community agroecology initiatives, already responsible for protecting biomes, ensuring food sovereignty, and tackling extreme climatic events, need to gain scale and visibility. For the participants, recognizing these practices as a central part of climate strategies is an essential step towards aligning environmental, economic, and social justice.

About Labora

Labora – Fund for Decent Work exists to support collectives, unions, and organizations committed to promoting decent work, social protection, and a just ecological transition.

The program supports actions that defend the rights of rural and urban workers, traditional peoples and communities, youth, women, migrants, and other vulnerable groups, especially those directly affected by the climate crisis, the precariousness of work, and rights violations.

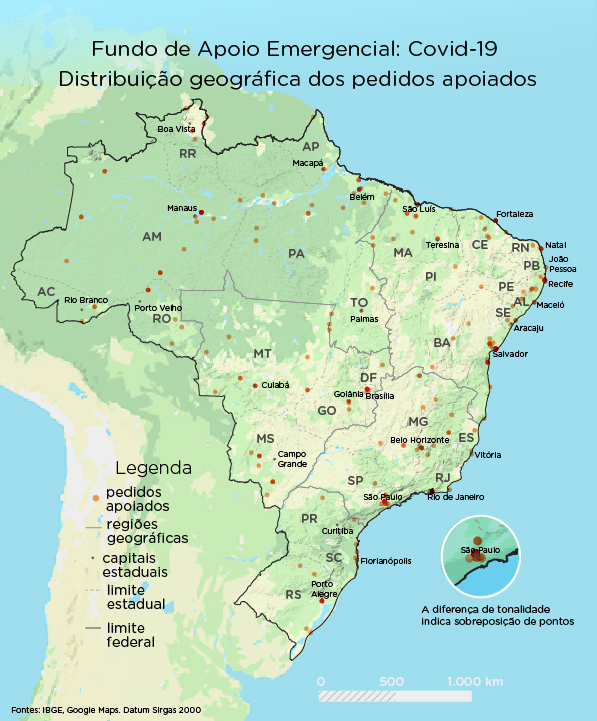

“In three years, Labora has already supported over 250 initiatives, granting approximately R$4 million to projects in agroecology, socio-environmental justice, and community strengthening,” reported Ana Valéria Araújo.