Photo: AMTCOB Collection

In the northeastern cerrado (a biome characteristic of inland Brazil), 345 km from Teresina, near the sources of the Parnaíba River, the long and arched leaves of the babassu palm trees protect the red earth soil, shelter the vegetation, feed the rivers and sustain the lives of generations of breaker women.

The slender, deep-rooted tree is shelter, food, security and, for the coconut breakers, a symbol of their fight for rights. “We say here it’s our mother. The babassu is our heritage, it’s who we are, our food, our profession. The palm tree protects us, protects the territory, and we protect it,” said Klésia Lima, who considers herself a breaker since her mother’s womb.

In Parnaíba, in Piauí, where these long trees shape the landscape, the coconut breakers are born guardians of the forest and its sacred fruit. They are also born heirs of a fight that spans decades.

Photo: AMTCOB Collection

The women and the palm trees are threatened daily by the advance of agribusiness into the babassu grove territories, surrounded by monocultures and the constant use of pesticides.

They also face farmers, their henchmen, their fences and, in many cases, gender-based violence that seeks to delegitimize women’s traditional knowledge and strength. “We face threats all the time, such as the fencing of the territory by farmers and land grabbers, and the advance of agribusiness. Men, who don’t accept women as protagonists of important causes.”

Each babassu tree felled by a farmer is an attack on the breakers’ way of life. “We understand that fighting for the babassu is fighting for life, fighting for territory, defending our identity, defending women’s rights,” emphasizes the breaker.

The hardships imposed on keeping the ancestral practice alive led Klésia and 120 other breakers from the region to unite and found the Association of Babassu Coconut Breaker Women from the Low Parnaíba in 2004. The headquarters are in the municipality of Esperantina, in the north of the state. “Our objective is to promote the organization of women, so they can claim their rights as citizens. We carry out actions to raise awareness about the preservation of natural resources and report crimes against the environment and women.”

Despite the daily challenges, the association has enabled them to become more than rural workers: they have become leaders, knowledge multipliers, and managers of the living forest.

They receive support from the Brazil Human Rights Fund through the Local Communities Fighting for Climate Justice call for proposal, an initiative of the Raízes – Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Fund for Climate Justice, created by the Brazil Fund, which acknowledges and supports those who are on the frontlines of the defense and promotion of human, socio-environmental and climate justice rights. “With this project, we aim to strengthen the fight for free access to the babassu groves and for the appreciation of local ways of life in the territories of northern and southern Piauí. We rely on these resources to ensure training, income, women’s protagonism, and environmental protection,” says Klésia.

The babassu and the breakers are one and the same fight

Throughout Piauí there are over 10,000 coconut breakers. They enter the forests with handcrafted baskets, generally made of babassu, where they gather the fruits. Sitting on the soil, to the sound of singing, they begin the small-scale extraction of the nut. Klésia explains that, from the babassu palm, everything is used by the breakers. “When we say that from the babassu nothing is lost and everything generates new products, we aren’t exaggerating. We use the straw to weave baskets, the leaves for house roofs, the shell becomes charcoal, even the trunk becomes fertilizer.”

Photo: AMTCOB Collection

From the small, brown, hard-shelled fruit, a lot of life sprouts. “We make oil, soap, lotion, milk, feed, cake, cookies, ice cream, and much more.” The breakers have created, over time, a productive and sustainable chain with around 50 subproducts from the babassu coconut. “Look at how much wealth there is in such a small fruit. That’s why, to us, it’s the most valuable good.” The babassu is around 10 centimeters.

Beyond a livelihood, the babassu is an identity. That’s why the resistance of the women in the babassu groves is also a fight for territory, water, forest and life. Many of these palm trees are on private lands, where farmers impose restrictions. “They put fences, even electric ones, around the areas where these trees are to stop us from harvesting the coconut.”

To prevent the free movement of breakers on their lands, many cattle breeders also turn babassu groves into pastures. “That is criminal. They devastate all nature and destroy, while we want to preserve and take care,” reinforces the association representative.

They know the fruit’s time. The cluster with the coconuts takes nine months to fall. And, to respect this process, the breaking of the coconut is manual. “Using machines may hasten this cycle and that would harm our sustainable relationship with the babassu groves.”

Klésia emphasizes that that’s why they insist on staying, on replanting, on teaching the young women the value of the babassu. “We want such an important tradition not to end. We want our younger girls to be able to live in the territory, to have a decent life from the babassu.”

The Association of the Coconut Breakers from the Low Parnaíba is part of the Interstate Movement of Babassu Coconut Breakers (MIQCB), which supports the work and actions of over 300,000 breakers throughout the North and Northeast.

As a main collective achievement, the MIQCB members’ fight became law. In 2022, the Free Babassu Law was approved. A legal framework that ensures local communities’ access to the babassu groves in public and private areas, the result of years of mobilization in partnership. It also prohibits the felling of the palm trees.

As well as free access to the babassu groves, the law includes recommendations for the care of the “palm mothers,” such as the prohibition of pesticides in the babassu groves or other damages, such as the cutting of the cluster, indiscriminate deforestation, burnings, or cultivation of plantations that may harm their development.

The babassu that grows stronger with partnerships

Photo: AMTCOB Collection

The challenge remains great to implement the Free Babassu Law in practice. But they remain organized in the defense of agroecological production and the environment. “We won’t give up fighting the advance of agribusiness and resisting the fences that try to limit us.”

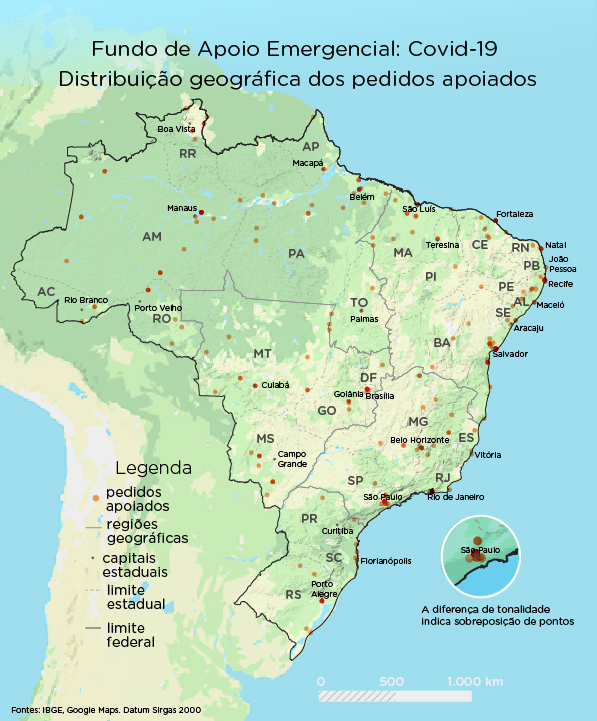

With support from the Brazil Human Rights Fund, the Association of Babassu Coconut Breaker Women from the Low Parnaíba has already held trainings for human rights defenders, leadership capacity building, workshops on babassu products, debates to raise awareness of rights, and panels on climate justice and the effects of climate change in the region.

Over 160 riverine, Indigenous and quilombola (local communities of descendants of enslaved people in Brazil) women have participated in the actions. Around 450 were indirectly impacted in the babassu coconut breaker municipalities of São João do Arraial, Luzilândia, Madeiro, Joca Marques, Esperantina, Morro do Chapéu, Antônio Almeida, Elizeu Martins and Cristino Castro, located in the north and south of the state of Piauí.

“The partnership with the Brazil Fund has been making a difference in the lives of the women. With the trainings, we started to see ourselves as rights-holders, to recognize ourselves as breakers with pride and strength. We are further strengthened, prepared and conscious to defend the babassu and our rights,” concludes Klésia Lima.