The smell of popcorn at the entrance of Cine Belas Artes, in Belo Horizonte, heralded the appointed date for Saturday evening, April 26th. The heritage-designated building in the neighborhood of Lourdes set the stage for the story that narrates the resistance and fight for rights by domestic workers, and marks the closure of the Tereza for Rights project.

The release of the documentary “Tereza for Rights”, realized by the Association of Domestic Workers Tereza de Benguela with the support of the Labora Fund for Decent Work, sold out the screening room of the only independent movie theater in the city, inviting around 80 people to reflect together about the subject.

Watch the teaser here.

Tereza for Rights project

In Brazil, the legislation that regulates domestic labor (Law nº 150/2015) defines as a domestic worker the one who provides services to the same family for over two days in a week. Bearing in mind the growing number of housekeeping domestic workers in the country, many of which do not fall into that legal criteria, and considering the high level of informality present in domestic labor in general, the Tereza de Benguela Association arose with the purpose to fight for legal guarantees, labor rights and dignified labor work conditions for that category.

Since its foundation, the group has been focused on the valuing of these workers, the defense of their labor rights, and the reclamation of specific public policies for the category. One of its central objectives is to transform the perception on domestic work, historically underrated by the Brazilian population.

In this context, the Tereza for Rights project sought to stimulate the public discourse around the guarantee of labor rights for housekeepers. Moreover, it earned its headquarters to offer direct support to the workers, to strengthen partnerships, and to integrate networks of social mobilization, with the final goal of expanding the association’s reach and the number of people supported.

At the end of the exhibition, the association promoted a debate with the inspectors of the Labor Inspection Office-SIT/MTE Cynthia Mara da Silva Alves Saldanha, Maria Fernanda de Faria Kindlé and Juliana Vilela Marcondes, mediated by Vitória Murta, coordinator of Tereza de Benguela.

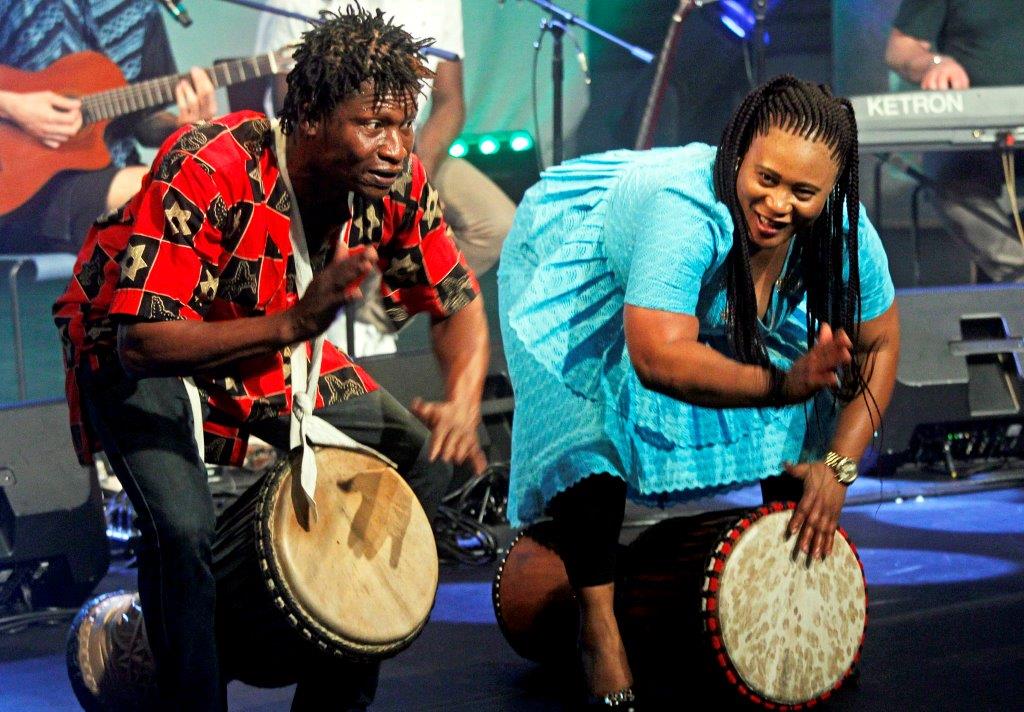

Release of the Tereza for Rights documentary, Belo Horizonte, 2025. Picture: Mariana Silveira/Brazil Fund Collection.

Debate with the inspectors Cynthia Mara da Silva Alves Saldanha, Maria Fernanda de Faria Kindlé and Juliana Vilela Marcondes, from the Labor Inspection Office-SIT/MTE, mediated by Vitória Murta. Picture: Mariana Silveira/Brazil Fund Collection.

To know more about the association’s trajectory, the documentary’s production process, and the project’s next steps, we interviewed Renata Aline, founder and president of the Tereza de Benguela Association. Read ahead:

How was the Association of Domestic Workers Tereza de Benguela born?

Renata: We came up in 2014 with the idea of fighting against exploitation. We thought the Housekeepers’ PEC (Project of Amendment to the Constitution), that was being voted, would solve the problem of exploitation of housekeeper women. In 2015, after the passing, we realized we had not been included. We started to understand that our first aim of fight should be exploitation and I, in that case, received the notifications and messages of people who wanted to hire a housekeeper. So, I determined: “look, the work hours are these, you will have to pay for food and transportation, they have to leave this way, you have to do this, don’t do that”. We would determine things. Until we understood it served nothing to keep only to this struggle if we didn’t ask for alteration or complementation to the Complementary Law 150. And today we got here, to the official release of the documentary about our history, 10 years later.

How was the documentary’s production? Which methodology did you use to get to this final product? Which is, by the way, really complete.

Renata: Tereza is not an institution that stays inside headquarters waiting for people to seek us or talk to us. We go to the communities, the buildings, the buses, and other cities to take our work and talk to these women who, sometimes, believe there’s no union or any type of entity that represents them.

We started to do this type of work, that was already our normal: active searches, mobilizations, and advocacies. We then invited Luan to record, who told us: “look, the documents are very good, I believe we can do something”. So, Vitoria had the idea to make the documentary, to get it all together. And then we started to work in 2023 with the following methodology: to show there is an association with a trajectory and a cause to tackle. We defined what we were going to address and started putting the documentary together. It happens that, in 2024, we weren’t selected in the project, but we received the money from MIPA and decided to continue with the advocacies that we were already conducting.

That’s where came in the stronger advocacy about labor similar to slavery. Up until then, we talked to the housekeepers and they complained a lot about rights’ violations and other matters. Suddenly, we started to receive reports of labor similar to slavery. We got to the locations and people started to report: “I started to work as a housekeeper because I was traded for a care package at eight years old”. We thought: “this is human trafficking, labor similar to slavery, child labor”. And we started to put together this chronological account as things developed within the institution. But nothing that was shown there is different from our daily work, because we’ve existed for 10 years.

What are the plans for the documentary?

Renata: From now on, our goal is to show the documentary in many different spaces. We have also received our first invitation, from the Viver Project, developed in Caucaia (Ceará), where we have a core with over 70 women, result of an exchange program undertaken by Labora. We will take the documentary there and have the same debate with the Public Prosecutor’s Office and other local authorities.

We understand the importance of reaching the widest public possible with this documentary, so that different places, such as São Paulo and others, may also screen it. We want to try to screen it in ALESP (São Paulo Legislative Assembly), because we realize the matter of the legal grey zone that affects housekeepers is scarcely tackled.

When we were approved by the Fund’s project it was curious, because we were approved alongside a union, but I was really afraid of speaking. It’s a delicate subject, scarcely discussed, as if the problem were already solved. Until I gathered courage and said: “no, people, I have an institution, it exists, people know I speak and fight for this, so I have to speak, even if someone disagrees”. I have to express I don’t have rights, because I was a housekeeper for 12 years. During this period, working in family homes, I didn’t have any social security contribution. That means I worked for 12 years without this time being acknowledged for my retirement. Nobody recognizes me as a worker.

That’s why I believe the documentary is an important tool for the country. Whoever wants to screen it, can invite us. The invitation is open to all of Brazil.

Recently, the organization takes part in the Municipal Plan of Care in Belo Horizonte. How has this construction been?

Renata: The construction of this plan’s principles was trailblazing in the country, being the first policy to be voted even before the publication of the national plan. Tereza participated in this construction, although with a quite contradictory perspective towards the mainstream discourse. We were invited with the following: “So, is everything ok? Do you think domestic labor should be extinct?”. Our answer was clear: domestic labor is essential and has to exist. However, we, housekeepers, have no plan of care of any kind.

The central question is that, if we aren’t nationally recognized workers, how does oversight and regulation take place? A formal worker is recognized by the Brazilian Occupations Classification (CBO), has her work post defined, is overseen and regulated. If we don’t match these pre-requisites, we can’t be overseen because, to the system, we don’t exist. We can’t get social security because there’s no specific code for our contribution.

In the face of that, what is the real purpose of this plan of care for us? We believe the plan of care should regulate and regularize us, ensuring the same rights that monthly regular laborers, who work up to thrice a week, already have. That’s care: ensuring rights and dignity. We learned with Labora the strength of the phrase “I have a right to decent work”. This decent work is intrinsic to care and fundamental to ensure the minimal rights of our work. This is our vision within the policy of care.

An often-debated theme after the documentary screening, and that is very present in the media because of the National Break, was the matter of uberization, platformization of work. How has the Tereza de Benguela Association tackled this theme?

Renata: In the scope of jurisdiction of uberization, it is crucial to tackle the growing reality of the uberized domestic labor. We were invited by the Brazil Fund to take part in the Latin-American Convention of Labor and Technology, in Rio de Janeiro, and were, alongside FENATRAD, the only voices representing that matter. This participation showed us that the debate on the uberization of domestic labor is still very limited.

Our studies and data tracking indicate that uberization, beyond intensifying precarization, may bring a significant obstacle to the regulation of the Complementary Law 150. The legislation on uberization focuses on app workers and other professions, such as Uber drivers, ignoring the reality of domestic labor in Brazil, as if it’s an already solved problem.

However, we know that domestic labor is one of the sectors with the least guaranteed rights. There is a resistance in all levels – legal, legislative, and even within the population – to recognizing domestic workers as subjects of rights. Many women who should be fighting for their rights don’t do it when they don’t recognize themselves as such.

It’s fundamental to bear caution, strengthen the foundations and conscientize the domestic workers about their rights. On the contrary, we run the risk of repeating what happened to the Housekeepers’ PEC that, despite having been an advancement, still faces low enforcement in terms of regulated work.

Therefore, the debate about uberization must include the reality of uberized domestic workers. We have to take part in the discussions and demonstrations about the rights of app workers, because we are a significant category and with important particularities, such as the difficulty in working the 6×1 scale. The resistance in granting Saturdays off showcases the hypocrisy of those who defend rights, but don’t apply them in their own houses.

We believe that those who fight uberization frequently forget about us, just as Congress did. We feel isolated in this matter, maybe because of class biases. It’s relevant to mention that we took the theme “uberization and the paths of domestic labor” to G20, invited by Labora, and had one of the largest discussion rooms. Lawyers present confirmed the invisibility of domestic labor in the debate about uberization, while uberized agencies profit off of precariousness without any regulation.

The uberization process in domestic labor is even more vile due to the lack of transparency. Differently from an app driver that knows the value paid by the passenger and their percentage, the housekeeper often lacks that information. A cleaning may cost an amount, but she receives another, without knowing the total sum. This lack of transparency, that should be guaranteed by law as it is in other categories, violates the human rights of domestic workers in an even deeper way.

A positive example of attention to the matter of uberization comes from Juiz de Fora, where city councilor Cida Oliveira was a trailblazer in creating the PL (Law Project) of uberization and recognizing the work post of app deliverers. We will aim to talk to her in order to understand the demand of uberized domestic labor in her region, since most reports about that mode come from Latin America, and in Brazil there’s still a great invisibility about the theme.

In the face of this scenario of exploitation of domestic workers in conditions similar to slavery, what are the main challenges identified by the organization in the rescue processes and, especially, in the post-rescue support of these women, considering the particularities of this kind of work and the State’s acting?

Renata: Our acting in the fight against work similar to slavery began with roundtable conversations in the communities. Through dialogue with the women, we noticed that many were underreported, that is, hadn’t been rescued or even identified by the State. We understand that, independently of formal identification, it was our duty to handle the aftermath of these women’s rescue. In Brazil, after-rescue is almost non-existent, referring to the process of reinsertion of these women, either in the labor market – guaranteeing their rights and alerting about inadequate conditions – or in other modes of earning. Opening shelters is a constant challenge due to the country’s resistance in institutionalizing this need. Sheltering a person for enough time that they get stronger and may move on is complex.

Upon rescuing a woman in conditions similar to slavery, we frequently find a lady whose situation is already deeply rooted. Often times, she lost family ties in childhood, when she started working in that house. Some don’t even want to leave that environment. Those women’s recue is always costly, because reports of domestic work are more difficult to enact due to the sanctity of the home and the difficulties of access to the victim, often requiring a forewarning that aids in the situation’s occultation. Consequently, the number of rescues of domestic workers is low. Most recues in the country happen in the rural sector, involving mostly men. Even in those cases, women – cooks and other helpers – are frequently abandoned. Moreover, many rescued rural workers end up migrating to other farms and being exploited again.

Within our institution, we have three women who are the aftermath of underreported rescues. Recently, we filed a complaint starting from an information from SUS (Brazilian Unified Healthcare). Our prevention work is intense, distributing informative flyers in health centers, CRAS (Welfare Centers) and CREAS (Specialized Welfare Centers) so that the population may identify and report cases. In this specific situation, a person was admitted into SUS in a grave state, reporting their exploitation, and SUS reached out to us. We forwarded the complaint to overseeing auditors and waited for providences. However, the number of effective rescues of domestic workers in relation to the number of reports is alarmingly low.

We rescued our first worker in 2017. The case of Madalena Gordiano, also rescued in 2017, is still the most notorious rescue event in Brazil so far. Currently, we follow up in Sônia’s case, who is also within rescue process. It’s always harder to rescue a woman, and I believe there’s a strong underlying racial and class matter that leads to the subjugation of Black women and the belief that they belong to that condition of servitude. In many cases, auditors rescue workers, but judges dismiss the cases as work similar to slavery, ignoring that even one of the elements foreseen in the Penal Code’s article 149 is enough to characterize it.

Considering the hardships faced, which initiatives and strategies has the organization been seeking out to obtain support and develop effective alternatives of shelter and support for those women?

Renata: This difficulty in obtaining legal recognition for the cases of exploitation brought us to debate the matter of uberization, that involves exhaustive work hours, something we also observed in the work of app drivers and deliverers who work over 20 hours a day with little to no rest. We received interesting proposals for the creation of a shelter that would be run by the very women assisted by Tereza. This initiative aims to provide them with a sense of usefulness, because many grew up believing that care is their only purpose and find it hard to get into other areas. The shelter would be a way of ensuring their living, allowing them to care for other women who faced similar situations.

Our goal is to sensitize the public power to the urgency of the question of work similar to slavery in the home environment and to the need of an effective after-rescue that guarantees the dignity and autonomy of these women. We believe conscientization and mobilization are essential ways of breaking the invisibility and impunity that still surround this serious violation of human rights.

Release of the Tereza for Rights documentary, Belo Horizonte, 2025. Picture: Mariana Silveira/Brazil Fund Collection.

Technical file of the documentary Tereza for Rights: for the social security of housekeeping domestic workers (2025)

Runtime: 58 min.

Copyright: Association of Domestic Workers Tereza de Benguela.

Script: Renata Aline and Vitória Murta

Executive Production: Júlia Vargas.

Direction and Co-Production: Luan Cândido e Ren Camey.

Funding: Labora Fund for Decent Work.

Also read: Glossary about what is Human Trafficking and the interview with the historian Wlamyra de Albuquerque, who is dedicated to the study of the immediate post-abolition period, from 1888 until the decade of 1930.